Tables

DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-164290/v1

Medical humanities use subjects traditionally known as the humanities for specific purposes in medical education. The arts and humanities have been argued to be important in the development of humane judgment (Ghias et al. 2020). Medical humanities programs have been offered for nearly five decades at medical schools in developed nations. These programs are, however, not common in developing countries, especially in South Asia.

MH programs are not common in Nepal, a developing country in South Asia. A voluntary module was offered to interested students at the Manipal College of Medical Sciences (MCOMS), Pokhara (Shankar, 2008). A module was offered to all first-year medical students at the KIST Medical College (KISTMC) in Lalitpur, Nepal (Shankar et al. 2010). The module named Sparshanam (which means touch in Sanskrit an ancient language of South Asia) used small group activities, case scenarios, role-plays, paintings, and debates to explore different aspects of MH. The module was offered to the first batch of students in 2009 and the authors of the manuscript were facilitators of the module.

There is a case for incorporating MH in the medical curriculum as it may produce more compassionate and empathetic doctors (Shapiro and Rucker, 2003). MH promotes medical communication and professionalism, hones observational skills and promotes reflection and self-care (Shapiro et al. 2009). There are several studies which evaluated the short-term impact of MH. At the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in the United States the Healer’s art curriculum improved empathy toward patients and peers, improved commitment to service and reduced burnout (Lawrence et al. 2020). At the Patan Academy of Health Sciences (PAHS), Nepal students had positive perceptions of the MH course, its importance and were of the opinion that it offered a different perspective about the disabled and on the value of human life and death (Helen et al. 2020). Student feedback on the module at KIST Medical College obtained immediately following the module was also positive (Shankar et al. 2011).

There are challenges in studying the medium and long-term impact of MH. The process is complex and is confounded by a variety of factors (Bleakley 2015). At Stanford Medical School in the United States (US), showed that the benefits of a bioethics and medical humanities (BEMH) scholarly concentration persisted into postgraduation (Liu et al. 2019). A physician educator identifies five domains in which MH affects students’ subsequent health professions training and practice (Barron, 2017). These are context and complementarity, clinical relevance, reflective practice, professional preparedness, and vocational calling. The author mentions MH serves to animate the basic sciences, emphasizes the personhood of both the patient and the practitioner, promotes students’ ability to engage in reflective practice, better prepares them for clinical education and professional training, and emphasizes medicine as a vocation, a calling.

A survey in 2010 found that only nine studies had looked at longer term implications of MH interventions (Ousager and Johannsen, 2010). The authors of that study concluded that evidence on the long-term impact of MH on professional behavior is sparse. The present study aimed to obtain the perception of the first batch of MBBS students about Sparshanam, the MH module conducted at KISTMC and its perceived impact on their personal and professional life. We collected this information after a period of twelve years since the course conclusion to understand how students perceive the effect of the module on their personal and professional life. Basic demographic information about the respondents, their perception about the strengths and areas requiring attention regarding the module they had attended, the influence of the module on their present work and skills and talents further developed by the module will be noted and their recommendations regarding MH learning in Nepalese medical schools were also ascertained.

The first batch of students who had joined the undergraduate medical (MBBS) program in November-December 2008 were invited to participate in an online survey. The first batch of students have an online Facebook group which was used by the authors to communicate about the survey. Online communication tools like Facebook Messenger were also used to establish contact and encourage alumni participation.

The questionnaire was prepared using Google forms and the link posted on the Facebook group and distributed through Messenger and email. Information about the study was provided and to refresh their memory important features of the medical humanities module, Sparshanam conducted in 2009 was also provided. The questionnaire was developed through consensus among the authors and an extensive review of the published literature. The questionnaire was sent to two experts for their inputs and modifications requested were carried out. Respondents provided their written informed consent to participate in the survey through the online form. They were assured about the confidentiality of the data collected and informed that only group data will be published.

The questionnaire consisted of six sections. The first section provided information about the study and obtained written, informed consent. The second section was about the strengths and weaknesses of the module as perceived by the respondents after a decade of exposure and experience as doctors, the third was about subsequent exposure to MH, the fourth about their current work and their involvement in facilitating learning of MH, the fifth explored contribution of the module to personal and professional development while the last section collected demographic information.

The questionnaire used in the study is shown in the Appendix. The demographic information collected was gender, specialization, nature of work, place, and country of work and marital status. The survey was kept open for a one-month period from the second week of December 2020 to the second week of January 2021. Reminders were sent to the participants at ten-day intervals.

The questionnaire was analyzed descriptively. The comments were noted and the frequency of mention of different comments was also noted. The demographic characteristics of the respondents was tabulated. The questionnaire was approved by the institutional review committee of KIST Medical College with reference number 077/078/04 dated 27th November 2020.

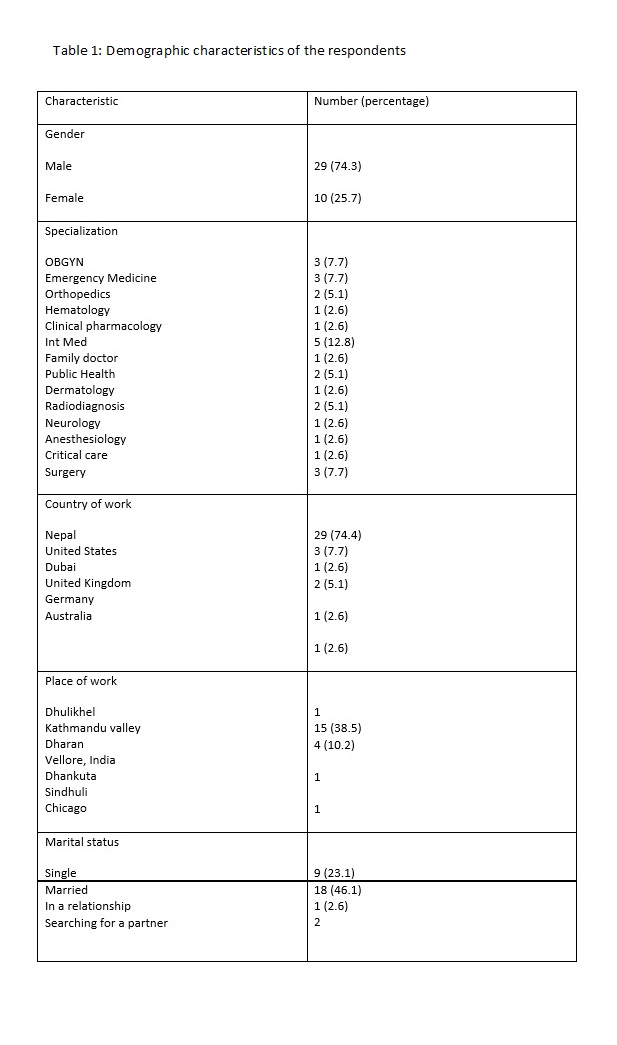

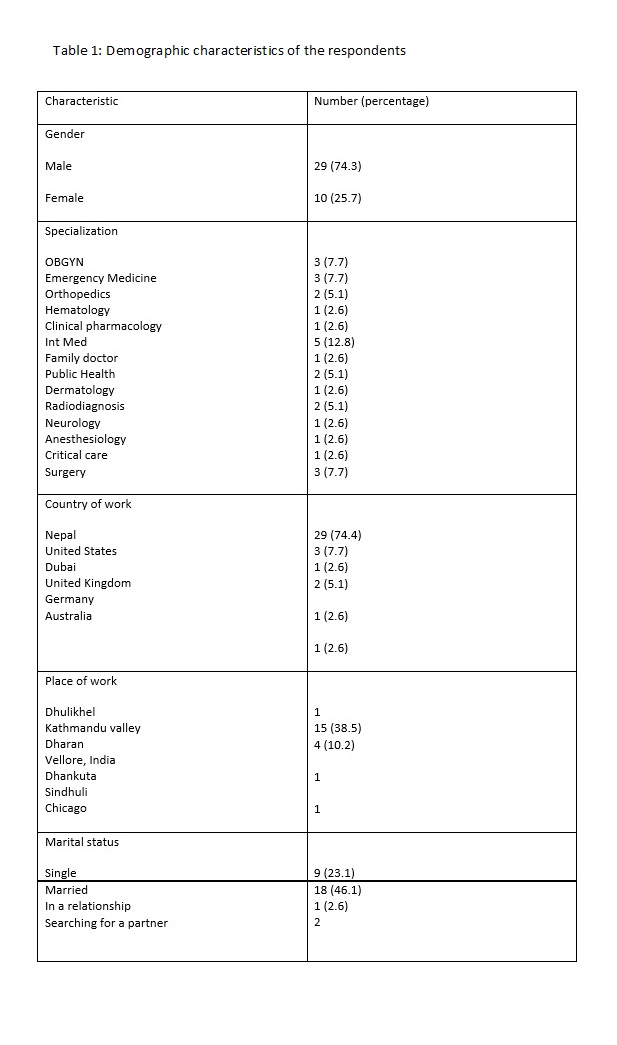

A total of 39 of the 75 (52%) first batch students participated. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the respondents. The number of male respondents was more. Maximum number of students are Internal Medicine specialists, majority are working in Nepal and within the Kathmandu valley. Most respondents are married.

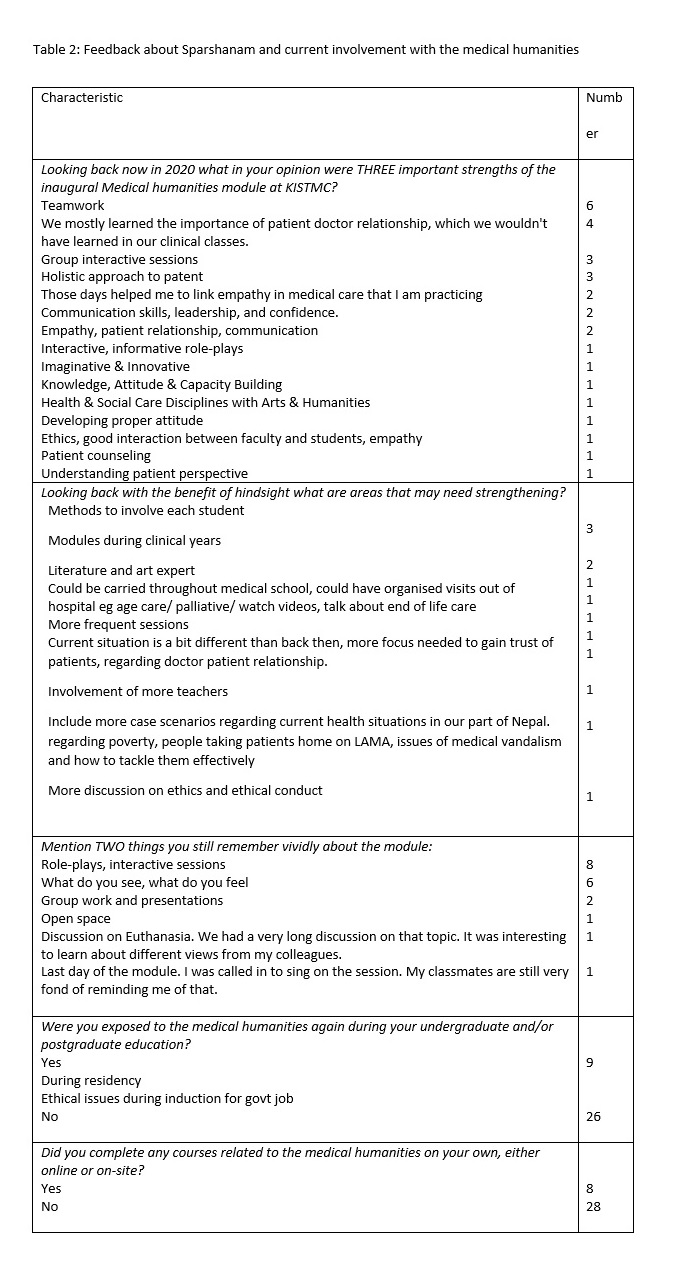

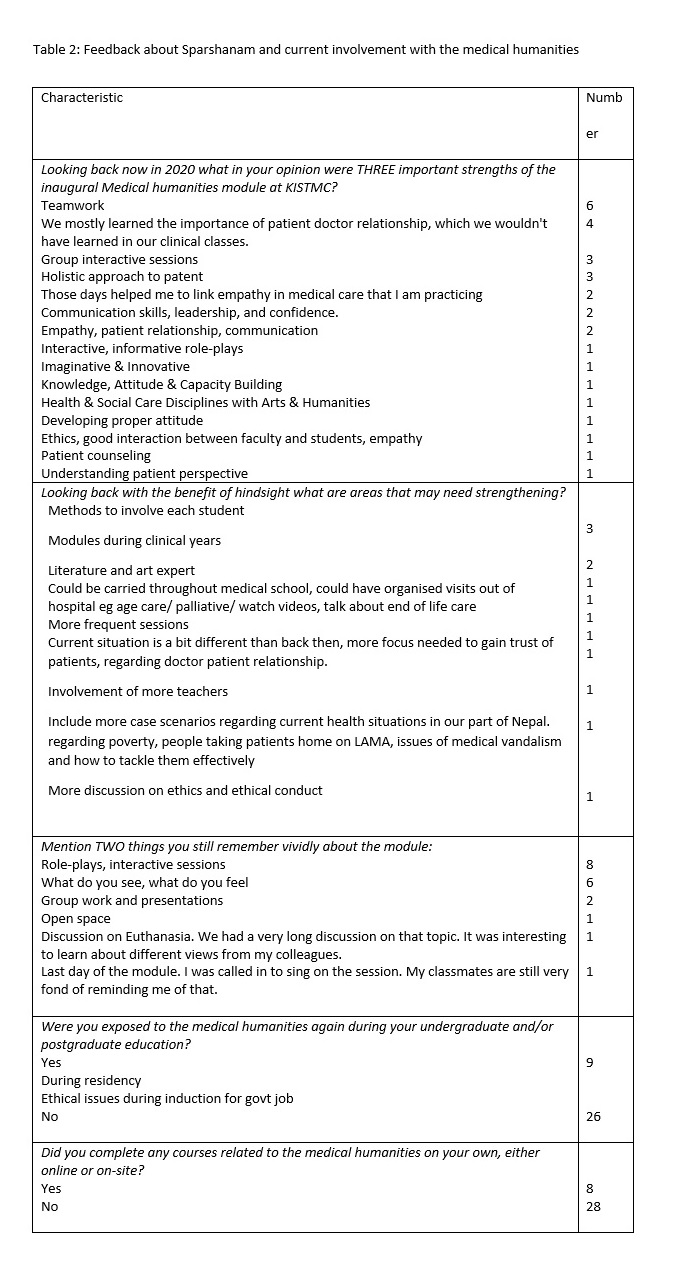

Table 2 shows respondents’ comments about Sparshanam and their current involvement with MH. Teamwork, importance of patient-doctor relationship, interactive group sessions and learning about a holistic approach to a patient were the most important strengths of the module. Among areas which may need strengthening were developing methods to involve each student during the module and conducting modules during the clinical years. Most were not exposed to MH again. Eight respondents completed courses/sessions related to MH.

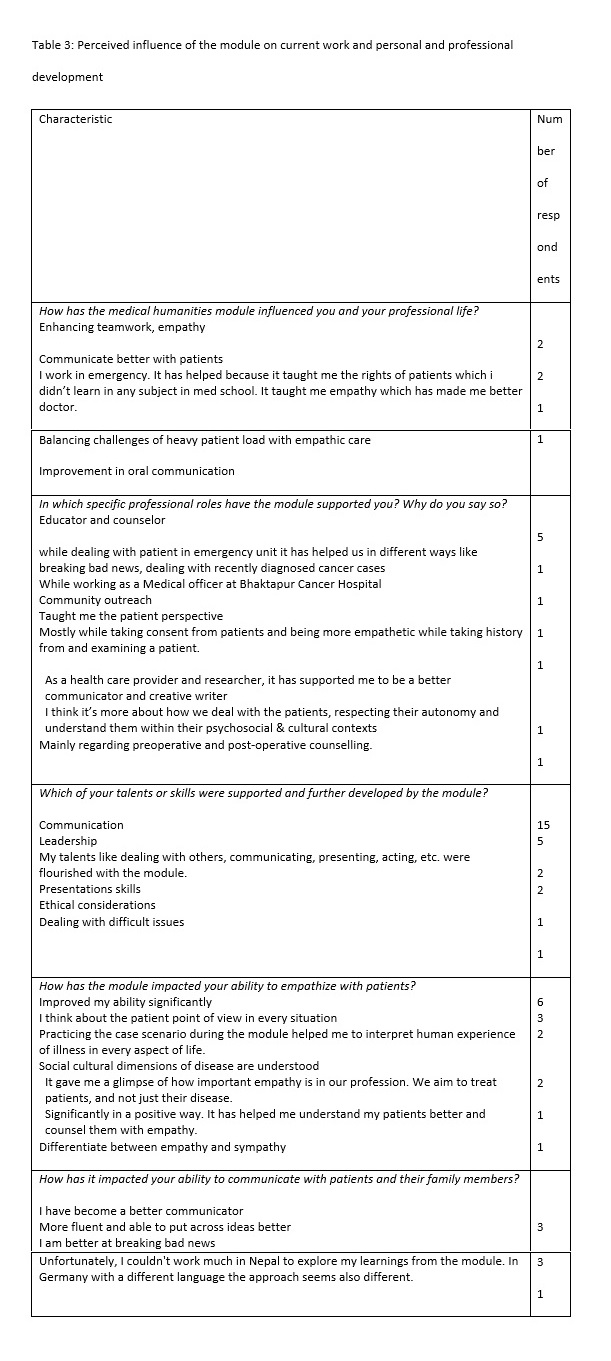

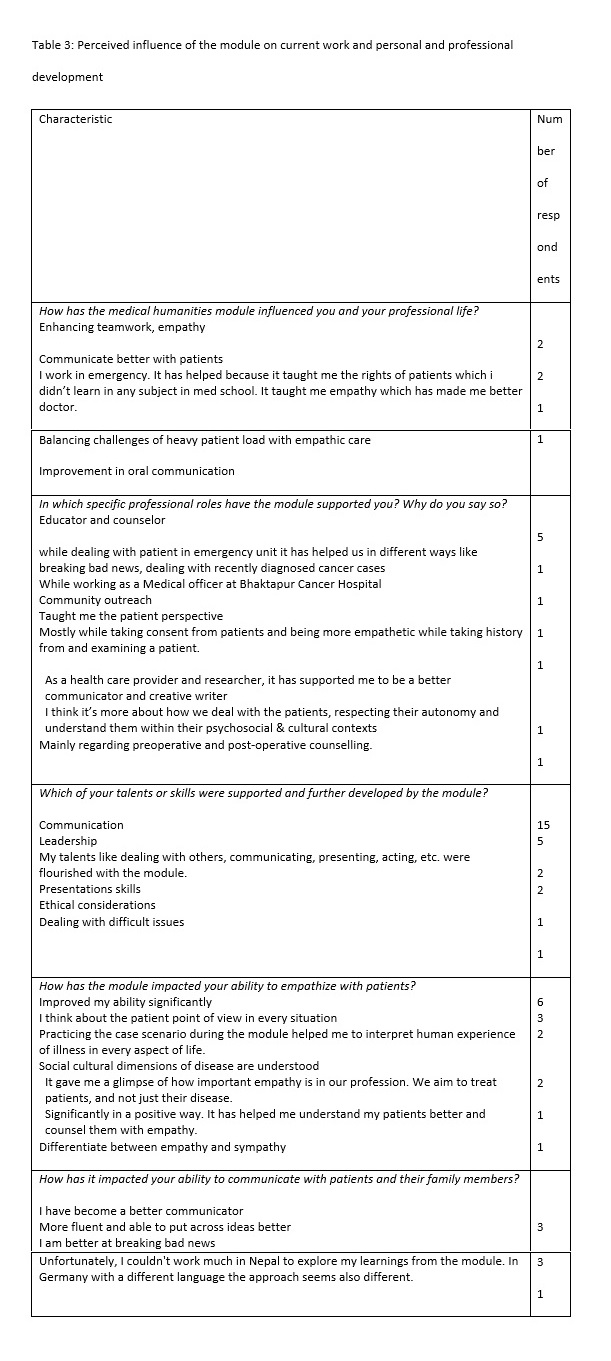

Table 3 deals with the perceived influence of the module on the respondents ‘current work and how it has influenced their personal and professional development. The module enhanced teamwork and their ability to empathize with patients and helped them to communicate better with patients. The module helped them to be better educators and counselors of patients.

A respondent mentioned, “When it comes to the critically ill, and during and after my post-graduation prior to surgeries as a part of the consent process as well as in explaining the pros and cons of every specific thing we do. Breaking bad news was an important component of the Medical Humanities module and it has assisted me greatly. Also, empathy, its limitations and putting on the professional hat to objectify treatment requires a balance. Humanities, in ways, helped me achieve that balance.” Another mentioned, “It has helped me in my day to day patient centred clinical care and my role as a Medical Doctors it has helped me a lot in my every walk. It has helped me in areas like dealing with empathy, respecting autonomy, proper counselling, breaking bad news and so on.” Their communication and leadership skills they perceived were supported and further developed by the module.14

Regarding their ability to empathize with patients, a respondent mentioned, “The module gave the concept of empathy and made us realise the situation that patient and patient party would go through during the difficult situation. I am now better at communicating during these difficult situations.” About their ability to communicate with patients most mentioned they have become better communicators. An alumnus mentioned, “I'm confident about what I say. I prepare my conversation with the family in my head beforehand and even when there is a difficult situation, I know I have the skill to tackle the problem. And if I cannot, I know when to seek help from seniors.”

Regarding the teaching of MH in medical colleges in Nepal, ten respondents mentioned it should be mandatory while six would strongly recommend it for inclusion. Three respondents wanted MH to be implemented during all stages of the medical program including postgraduation.

Among other comments were “More integration into the current syllabus, and classes specifically focused on communication in Nepali language with patients. We find it difficult to explain things to patients who do not speak English.”, “Very few centers are privileged to be part of such wonderful program. I think this should be part of curriculum throughout medical education.”, and “Like we had during our studies time the roleplays using pictures, scenarios etc. This should be a part of our course as it has very broad use for lifetime and it teaches us various ways how to use the knowledge that we have learnt from books.”

Regarding how the module developed their clinical observation skills the observations of the respondents were “Three aspects of the module what I see, what I feel and what I think is the basis for every clinical observation”, “These modules taught us to see the patient as a whole and not only the disease but also its impact in his/her life.” and “Supported to understand the importance of observation to move ahead in the clinical examination hence focus on observation during clinical practice.” The skills of reflection were developed through the exercises and activities associated with the module.

About how the module has developed their teamwork abilities their comments were, “A lot. The groups and the teamwork we did during those session has taught me how different minds can be utilized to generate ideas and solution to tackle the situations.”, “Group work and discussions in the medical humanities helped me understand and respect the difference in between individual” and “Teamwork was one of the pillars of this program. It has always emphasized how each member is valuable and respecting each other's idea and company.” Ten alumni were pursuing their postgraduation/residency.

Alumni feedback about the MH module was positive. They had participated in the module in 2009 and feedback was collected during December 2020-January 2021. Over half the batch participated in the survey. Most respondents were working in Nepal within the Kathmandu valley. Teamwork and the interactive group sessions were the most important strengths. Respondents believed the module enhanced their ability to see the patient as a whole and their ability to empathize and communicate with patients. Leadership skills were also developed. Most respondents wanted MH to be introduced in all medical colleges and opined that their observation skills were also strengthened. Most are not involved in teaching MH to others at present.

The module ‘Sparshanam’ used small group activities, clinical scenarios, presentations, role-plays, paintings among other modalities to explore MH (Shankar et al. 2010). Many students who had completed the module are now practicing doctors while others are doing their postgraduation. Most of the graduates are still working in Nepal which may be a good sign regarding doctors for Nepal. Most Nepalese doctors migrate or plan to migrate to developed nations. In a study published in 2009 almost half the interns and house officers planned to migrate to a developed country (Lakhey et al. 2009). Most graduates were working in the Kathmandu valley. Most doctors prefer to work in urban Nepal and especially the Kathmandu valley due to a variety of factors. However, only half the student population was recruited in the present study and it may be possible that those who did not participate may be working outside the valley.

According to the respondents, the most important strengths of the module were teamwork, importance of patient-doctor relationship, interactive group sessions and learning about a holistic approach to a patient. These individuals have been involved in both supervised and independent clinical practice for over a decade and they opined that the module helps them during their clinical work. In a study at Stanford Medical School respondents reported being more comfortable discussing autonomy, ambiguity and being better at facilitating team communication (Liu et al. 2018). Respondents believed the module helped them to better empathize and communicate with patients and to be better educators and counselors. Promoting and maintaining empathy has been mentioned in many studies as an important objective of MH. Most of medicine emphasizes pathophysiology but MH emphasizes the personhood of both the patient and the practitioner and can act as a ballast to the dominance of science (Barron, 2017). This is also highlighted by another article on the impact of MH (Wershof Schwartz et al. 2009). Recently our concept of empathy has changed from a static inborn trait to a learnable neurobiological competency (Riess 2017). Empathy related training may activate the relevant brain structures and fostering empathy should be a priority within medical education (Shalev and McCann 2020).

MH is still not common in medical colleges in Nepal. On doing a literature search we were able to find only the module from PAHS in addition to our own initiatives at KISTMC and MCOMS. From informal discussions a few other initiatives are underway like a general book club at the Institute of Medicine, the oldest medical school in the country. A preprint from PAHS demonstrates that the module had increased empathy among the students who had participated (Krishna, G.C., Amit Arjyal, Amanda Douglas, Madhusudan Subedi, and Rajesh Gongal. 2020. “A quantitative evaluation of empathy using JSE-S tool, before and after a medical humanities module, amongst first year medical students in Nepal.” Research Square https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-128016/v1 Available from: https://assets.researchsquare.com/files/rs-128016/v1/61d1907d-ed1c-4d0a-a9d1-2ba80dbeddd8.pdf ). Participants opined that the module had developed their clinical observation skills. Critical analysis of art and visual thinking strategies (VTS) have been shown to increase clinical diagnostic skills (Chisolm 2020). A recent review mentions that results consistently indicate that participants find that the incorporation of art into medical curricula was beneficial (Dalia et al. 2020).

Teamwork and leadership skills are important and in Nepal many medical graduates may have to administer a primary healthcare center or a community hospital after graduation. In 2005/2006 a scholarship with a requirement for rural service following graduation was introduced and has partly alleviated the shortage of doctors in rural Nepal (Mahat et al. 2020). Teamwork and leadership skills learned during the module are further strengthened during the community diagnosis and other postings and pre-service training. Understanding and respecting the perspective of another individual (including team members, administrators, and patients) is especially important in Nepal which is a very diverse country with a variety of ethnic and caste groups. During their rural service doctors may be posted in communities and environments which are significantly different from their own. ‘Open space’ was an activity toward the end of each module where we allowed participants to express their creative talents through different activities like reciting a poem that they have written or singing a song or even playing an instrument. This was well received by the participants and as mentioned by a respondent was an important part of the module. These creations were mostly in Nepali, the national language. Due to various reasons, the language of medical education and of the medical humanities module in Nepal is English. The role plays were mostly conducted by the participants in Nepali.

The long-term effect of MH is difficult to measure due to a variety of factors. A review examined 245 published studies between 2000 and 2008 on the humanities in undergraduate medical education (Ousager and Johannessen 2010). Only nine articles showed evidence of attempts to measure long-term impact. Peters et al. compared two groups of Harvard graduates and showed that graduates from the new humanities-oriented pathway performed better in the domain of humanistic medicine (Peters et al. 2000). DiLalla and colleagues claimed in their study that exposure to educational activities in empathy, philosophical values and meaning, and wellness during medical school may increase these in practice (DiLalla et al. 2004).

Our study has limitations. The response rate was low. It was challenging to involve students in an online study as they found it difficult to commit time due to their other commitments and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. We did not objectively measure empathy and other traits among students. We have a baseline measure of empathy among these group of students (Shankar and Piryani 2013) and can consider this in future. Respondents’ perception was measured using a questionnaire and not triangulated with information obtained from other sources.

Participants’ feedback about the module continues to be positive over a decade after it was offered. They were not exposed to a formal course on MH after the module. Respondents opined that the module had a significant impact on their group working, leadership and clinical diagnostic skills. They were able to obtain a holistic perspective on the patient and to be better educators and counsellors. They wanted a MH module to be introduced at all medical schools in Nepal. They opined that the module had a significant effect on their long-term personal and professional development. MH modules are still not common in Nepal so the results from this module may serve as a facilitating factor to introduce MH in the undergraduate medical curriculum.

Funding: There was no funding for this work.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Availability of data and material: Information from the study has been provided in the manuscript.

Code availability: Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

|

Contribution |

PRS |

AKD |

RMP |

DS |

YPD |

|

Conceptualization |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Review of literature |

x |

x |

x |

|

|

|

Liasing with the alumni |

x |

x |

|

x |

|

|

Data collection |

x |

x |

|

|

|

|

Analyzing the data |

x |

|

x |

|

x |

|

Interpreting the data |

x |

x |

|

x |

x |

|

Writing the manuscript |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Revising the manuscript |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

Approval to publish |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

Ethics approval: Institutional review committee of KIST Medical College with reference number 077/078/04 dated 27th November 2020.

Consent to participate: Dear graduates We are collecting your feedback about Sparshanam, the Medical Humanities module, and the possible influence of the module on your personal and professional life. I consent to participate in the study. All information will be used for the study purposes only and no individual identifying information will be presented.

Consent to publish: Dear graduates We plan to publish the study findings and only group data will be published. Individual identifying data will not be published. I consent to the publication of the study findings.

Acknowledgements: The authors acknowledge all graduates who participated in the study.

Barron, Lauren. 2017. “The Impact of Baccalaureate Medical Humanities on Subsequent Medical Training and Practice: A Physician-Educator's Perspective.” Journal of Medical Humanities 38(4): 473-483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-017-9457-1

Bleakley, Alan. 2015. “Seven Types of Ambiguity in Evaluating the Impact of Humanities Provision in Undergraduate Medicine Curricula.” Journal of Medical Humanities. 36(4): 337-357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-015-9337-5

Chisolm, Margaret S., Margot Kelly-Hedrick, and Scott M. Wright. 2020. “How Visual Arts-Based Education Can Promote Clinical Excellence.” Academic Medicine https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003862 Epub ahead of print.

Dalia, Yoseph, Emily C. Milam, and Evan A Rieder. 2020. “Art in Medical Education: A Review.” Journal of Graduate Medical Education 12(6): 686-695. https://doi.org/10.1097/10.4300/JGME-D-20-00093.1

DiLalla, Lisabeth F., Sharon K. Hull, and Dorsey J. Kevin. 2004. “Effect of gender, age, and relevant course work on attitudes toward empathy, patient spirituality, and physician wellness.” Teaching and Learning in Medicine 16(2): 165-170. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328015tlm1602_8

Ghias, Kulsoom, Kausar Saeed Khan, Rukshana Ali, Shireen Azfar, and Rashida Ahmed. 2020. “Impact of humanities and social sciences curriculum in an undergraduate medical education programme.” Journal of Pakistan Medical Association 70(9): 1516-1522. https://doi.org/10.5455/JPMA.24043

Helen, Amanda D, Madhusudan Subedi, and Rajesh Gongal. 2020. “Medical Undergraduates' Perceptions on Medical Humanities Course in Nepal.” Journal of Nepal Health Research Council 18(3): 436-441. https://doi.org/10.33314/jnhrc.v18i3.2568

Lakhey M, Lakhey, S, Niraula, SR, Jha, D, and Pant R. 2009. “Comparative attitude and plans of the medical students and young Nepalese doctors.” Kathmandu University Medical Journal 7(26): 177-182. https://doi.org/110.3126/kumj.v7i2.2717

Lawrence, Elizabeth C., Martha I. Carvour, Christopher Camarata, Evangeline Andarsio, and Michael W Rabow. 2020. “Requiring the Healer's Art Curriculum to Promote Professional Identity Formation Among Medical Students.” Journal of Medical Humanities 41(4): 531-541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-020-09649-z.

Liu, Emily Yang, Jason Neil Batten, Sylvia Bereknyei Merrell, and Audrey Shafer. 2018. “The long-term impact of a comprehensive scholarly concentration program in biomedical ethics and medical humanities.” BMC Medical Education (1): 204. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1311-2

Mahat, Agya, Mark Zimmerman, Rabina Shakya, and Robert B. Gerzoff. 2020. “Medical Scholarships Linked to Mandatory Service: The Nepal Experience.” Frontiers Public Health 8: 546382. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.546382

Ousager, Jakob, and Helle Johannessen. 2010. “Humanities in undergraduate medical education: a literature review.” Academic Medicine 85(6):988-998. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181dd226b

Peters, Antoinette S., Rachel Greenberger-Rosovsky, Charlotte Crowder, Susan D Block, and Gordan T Moore. 2000. “Long term outcomes of the New Pathway Program at Harvard Medical School: A randomized controlled trial.” Academic Medicine 75:470–479Riess, Helen. 2017. “The science of empathy.” Journal of Patient Expierence 4: 74–77.

Shalev, Daniel, and Ruth McCann. 2020. “Can the Medical Humanities Make Trainees More Compassionate? A Neurobehavioral Perspective.” Academic Psychiatry 44(5): 606-610. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-020-01180-6

Shankar, P Ravi. 2008. “A voluntary Medical Humanities module at the Manipal College of Medical Sciences, Pokhara, Nepal.” Family Medicine 40: 468-470.

Shankar, P Ravi, Rano M Piryani, Trilok P Thapa, and Balman S Karki. 2010. “Our Experiences With ‘Sparshanam’, A Medical Humanities Module For Medical Students At KIST Medical College, Nepal.” Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 4: 2158-2162.

Shankar, P Ravi, and Rano M Piryani. 2013. “Changes in empathy among first year medical students before and after a medical humanities module.” Education in Medicine Journal 5: e35-e42.

Shankar, Ravi P., Rano M. Piryani, and Kshitiz Upadhyay-Dhungel. 2013. “Student feedback on the use of paintings in Sparshanam, the Medical Humanities module at KIST Medical College, Nepal.” BMC Medical Education 11: 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-11-9

Shapiro, Johanna, and Lloyd Rucker. 2003. “Can poetry make better doctors? teaching the humanities and arts to medical students and residents at the University of California, Irvine, College of Medicine.” Academic Medicine 10: 953-957.

Shapiro, Johanna, Jack Coulehan, Delese Wear, and Martha Montello. 2009. “Medical humanities and their discontents: definitions, critiques, and implications.” Academic Medicine 84: 192–198.

Wershof Schwartz, Andrea, Jeremy S. Abramson, Israel Wojnowich, Robert Accordino, Edward J. Ronan, Mary R. Rifkin. 2009. “Evaluating the impact of the humanities in medical education.” Mt Sinai Journal of Medicine 76(4):372-380. https://doi.org/110.1002/msj.20126