Methods

Kebbi is a state in the north-western part of Nigeria. The 2019 projected population of Kebbi State was 4,671,594 while the under-five population was 2,223, 679. It has 21 Local Government Areas (LGAs), 225 political wards, and 122 districts spread over four emirate councils namely Argungu, Gwandu, Yauri, and Zuru. Seventy percent of the people live in rural communities, where the predominant economic activities are fishing, farming, and trading. There are 22 general hospitals, 225 primary health care centres, a Federal Medical centre, and a Specialist Hospital. In total, there are 203 focal sites for AFP which include all the secondary and tertiary public health facilities. And all the facilities offering routine immunization (RI) services offer free RI services.

Study tools and data management

i. Qualitative study

A structured self-administered questionnaire, adapted from previous similar studies and adapted for this study was used to obtain information from respondents (these are some of the respondents; State Epidemiologist, State DSNO, Assistant State DSNO, LGA DSNOs/ADSNOs). This is to assess their views on some of the surveillance system attributes (such as the simplicity, flexibility, representativeness, stability, usefulness, and acceptability of the system) 4,15–20.

ii. Quantitative study

A KII was conducted among some Key informants which include the SE, State DSNO, and some randomly selected three Medical officers from the State general hospitals as well as the WHO surveillance focal person in the State. These were to obtain more information regarding acceptability, stability, representativeness, and challenges faced.

iii. Review of documents

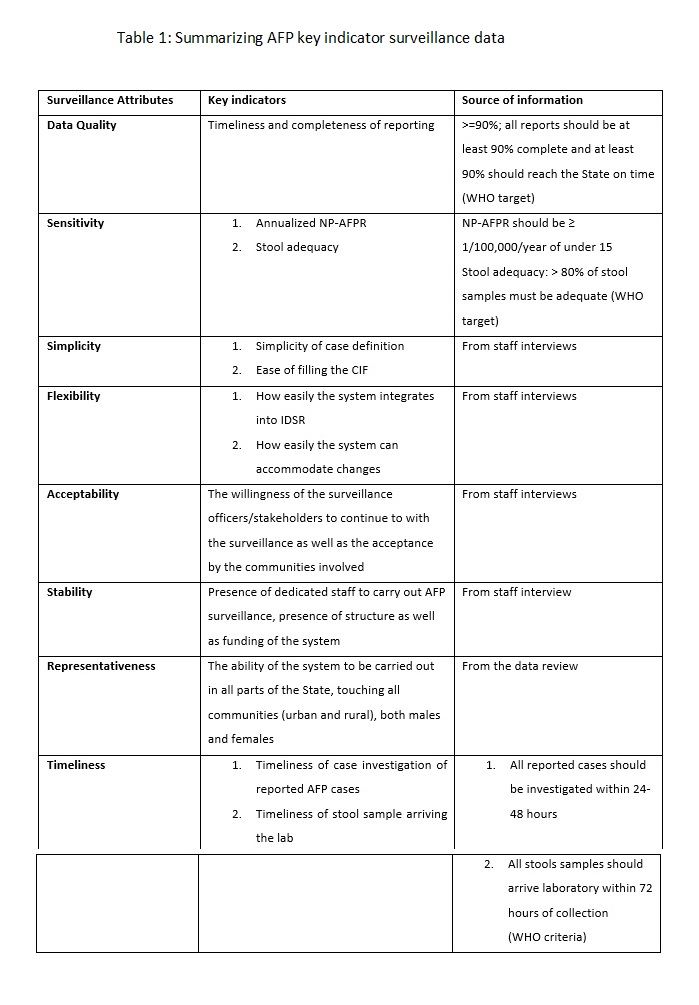

We also used the WHO standard guidelines for AFP performance standards to assess some of the attributes such as the sensitivity, timeliness, data quality, of the system. Some of these WHO from the data obtained on AFP surveillance in Kebbi State within the review period. The WHO guidelines are:

Indicators of AFP surveillance performance

- Percentage of all expected monthly reports that were received: target >=90%

- - Annualized non-polio AFP rate per 100 000 children under 15 years of age: target >=1/100 000

- Percentage of AFP cases investigated within 48 hours: target >=80%

- Percentage of AFP cases with two adequate stool specimens collected 24-48 hours apart and <=14 days after onset: Target = ≥ 80%

- Percentage of specimens arriving at the laboratory in good condition: target >=80%

- Percentage of specimens arriving at a WHO-accredited laboratory within three days of being sent: Target >=80%

- Percentage of specimens for which laboratory results sent within 28 days of receipt of specimens: Target >=80% 7

Data analysis

- We cleaned, coded, and analysed the quantitative data we obtained from the self-administered questionnaires. Using IBM SPSS version 25

- We used Microsoft excel to co conduct a secondary data analysis of the AFP surveillance data between January 2013 to December 2018.

- For the qualitative data obtained we conducted a thematic analysis.

A key informant interview (KII) guide also adopted from similar studies (22), was used to gather information from relevant stakeholders (State epidemiologist, Medical officers, and Monitoring & Evaluation officers) to also gather information on stability representativeness, funding, and other challenges facing the system. Those selected for KII include: Kebbi state Epidemiologist, Deputy State DSNO, Chief Medical Officers in General Hospital Zauro and General Hospital Zuru.

A retrospective record review of the AFP surveillance data from 2013-2018 was carried out. We used the data to determine the sensitivity, timeliness, representativeness of the system. We assessed data quality, by determining the timeliness and completeness of reporting. Completeness was assessed by estimating the proportion of complete weekly reports that got to the State by close of work (4.00 pm) of Tuesday of the reporting week. Representativeness was calculated by determining the proportion of all the health facilities that report.

AFP notified cases aged <15 years old between January 2013 and December 2018 were analysed. The analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel version 2016. Evidence regarding performances were assessed using system attributes according to the CDC updated guidelines to describe the attributes of the surveillance system.

Ethical consideration

Permission was obtained from the Kebbi State Ministry of Health Ethics Committee. The participants (stakeholders) were interviewed privately and confidentiality of data was maintained. A written permission was also obtained from the Public Health Department of the Kebbi State Ministry of Health (doc no; MOH/STA/PER/6007/205751). Written consent was also obtained from the study participants as indicated in the questionnaire.