Methods

Search strategy

The study protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), the University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (ID number: (CRD42019137013). This review and meta-analysis were conducted according to the guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) (16) (Additional file 1).

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria

Setting

Only quantitative studies done in Ethiopia were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Language

Only articles published in English were retrieved for review, given language restrictions will not affect the outcome of the study.

Publication condition

Both published and unpublished articles were considered for this review.

Exclusion Criteria

Studies for which we are unable to get the necessary details after contacting the authors were excluded. Studies on intranatal care were also excluded.

Information sources and search strategy

The following databases were searched to find potentially relevant articles: PubMed, Hinari, and Google Scholar. No date limit was applied. Google hand search and National University Digital Libraries such as electronic library of Addis Ababa University were searched to include gray literature. Hand search strategies of the reference lists of all included studies were also conducted. Afterward, the identified articles were directly transferred to Endnote citation manager software. Search terms like “magnitude, or “prevalence”, or “determinants”, “or “associated factors," and "antenatal care," or “prenatal care," and “satisfaction” were used. Examples of search strategy fit for all the databases searched are available in the supporting information (Additional file 2).

The following procedures were followed in this systematic review. First, the electronic databases search results were imported into the reference management software (Endnote citation manager) and all duplicates were removed. In the second step, all articles were screened by their title, abstract, and full text for eligibility against the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Third, a full document manuscript review was conducted and studies were removed through the predefined exclusion criteria. Finally, included articles were evaluated based on the Joana Brigg’s Institute (JBI) quality assessment tool (17, 18).

Data Extraction

Data charting process was done independently by using a Microsoft excel format. The data extraction form included the name of the author, year of publication, regions where the study was conducted, sample size, response rate, setting, and type of study design. The log odds ratios with 95% confidence interval for included variables were extracted in a binary format.

Risk of bias

The quality of each article was appraised by using the Joana Brigg’s Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist for cross-sectional studies having eight checklist items.

Cross-sectional studies: were assessed using JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies (17). The checklist has 8 parameters: 1) were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined, 2) were the study subjects and the setting described in detail, 3) was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way, 4) were objective, standard criteria used for the measurement of the condition, 5) were confounding factors identified, 6) were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated, 7) were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way, and 8. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? All articles had a high score and all of them were included in the study.

Data synthesis

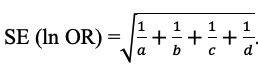

The odds ratio for determinant data were computed by pooling odds ratios reported in the original studies and standard errors (SE) for natural logarithm of odds ratios (ln OR) were calculated using the formula

The heterogeneity of reported pooled odds ratios was assessed by computing Cochrane Q-statistic and I2statistics. I2 test statistic results of 25%, 50%, and 75% were declared as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively (19). STATA version 14 software (StataCorp LP.2015, College Station, TX: USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Publication bias

Egger’s test was used to assess publication bias. A P-value of less than 0.05 was used to declare the publication bias.