Results And Discussion

The characteristic of Teenage Mother

The age of the teenage mothers were 15-19 years old, with 75% is for 17-19 years old and 25% is for 15-16 years old. Their educational background were primary school (50%), secondary school (37,55%), and high school (12,5%). None of teenage mother had underweight (81,25% of them had normal nutritional status, 12,5% of them had overweight, and 6,25% of them were obese). The majority of teenage mother were housewives (93,75%) and they are still living with parents (93.75%). The majority of teenage mothers (81.25%) were not ready to get married. Only there were 18.75% of teenage mothers who had been married because of own willingness. Other reasons were unwanted pregnancy (56%), demands of the parents (12,5%), and arranged marriage (12,5%). The unwanted pregnancy can be caused by promiscuity (pre-marital sex) with their boyfriend.

There are three stages of adolescence, which are the beginning of adolescence period (10-13 years old), the middle of adolescence period (14-16 years old), the final of adolescence period (17-19 years old).7 An early marriage and pregnancy affect on the psychosocial complication.16 The teenage mothers often feel anxious about their new responsibility as a mother.17 They feel uncomfortable among their peers, outcasted from the joyful activities, and forced to enter adulthood early.

The Breastfeeding Activities of Teenage Mother

The implementation of Early Breastfeeding Initiation, the provision of pre-lacteal food, colostrum, breastmilk substitution or early complementary food, as well as the pattern of breastfeeding by the young mothers are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Breastfeeding Activity of the Teenage Mothers

|

The Breastfeeding Activity of the Teenage Mothers (N=16) |

n |

% |

|

The implementation of Early Breastfeeding Initiation: Yes No |

11 5 |

68.75 31.25 |

|

Provision of Pre-lacteal Food: Yes No |

10 6 |

62.5 37.5 |

|

Provision of the Colostrum: Yes No |

13 3 |

81.25 18.75 |

|

Provision of Complementary Food/ Early Breastmilk Substitution: Yes No |

15 1 |

93.75 6.25 |

|

The Pattern of Breastfeeding: Partial Breastfeeding Predominant Breastfeeding Stopped Breastfeeding |

13 1 2 |

81.25 6.25 12.5 |

Table 1 shows that Early Breastfeeding Initiation is not implied to all mothers. The majority of the teenage mothers has provided pre-lacteal food and complementary food or early breastmilk substitution. During the research, the majority of the teenage mothers still breastfeed. Nevertheless, they did not breastfeed exclusively.

The Implementation of Early Breastfeeding Initiation

Table 1 shows that the majority of teenage mothers (68.75%) have approved the implementation of Early Breastfeeding Initiation in the maternity hospital. Nonetheless, there are 2 of 10 regulations which are not implemented properly by the maternity hospital workers. The first, the baby had been given the opportunity to search for the nipple, but not to find the nipple. The process of searching for a mother's nipple lasted only 10-30 minutes. According to the theory, the first 38 minutes are the stage of the quiescent state of alert, and occasionally the infant would open his eyes to see his mother. Between 38-40 minutes: the infant would make some noises, such as the mouth movement craving for breastmilk, and then he would kiss, lick the hand and then spill out his saliva, begin to move toward the breast, and find, lick, suck the nipples, open mouth, and get breastfed well.18 The second, it is about the father’s support in order to help mothers recognize the signs or the baby's behavior before getting breastfed. It has not been implemented properly.

During the prenatal period, there is only 1 of 16 teenage mothers (6.25%) got socialization about early breastfeeding. In fact, the result of quantitative research conducted by Raharjo (2014) showed that the role of the midwives affects to the implementation of early breastfeeding.22

The Provision Pre-lacteal Food, Colostrum, and Provision of Complementary Food or Early Breast-milk Substitutes

Table 1 shows that the majority of infants (62.5%) received pre-lacteal food such as sugar water, mineral water, honey, or formula milk. A total of 43.75% infants received it from the the labor force, while 18.75% of infants got pre-lacteal food from the family.

The majority of teenage mothers (81.25%) also provided colostrum. A total of one teenage mother (6.25%) did not provide colostrum because the infant was sleeping. Meanwhile, two other teenage mothers (12.5%) did not give colostrum due to the smell, taste, and its shape. In fact, the colostrum contains living cells resembling white blood cells to kill germs.20

The majority of teenage mothers (93.75%) provided Complementary Food or Breastmilk Substitution too early. Their infants (46.67%) were served complementary food or breastmilk substitution in under one month age. Besides the labor force, giving complementary food or breastmilk substitution too early also due to the suggestion from the closest relatives, especially the mother. Only 2 of 16 teenage mothers (12.5%) who provided complementary food or breastmilk substitution too early willingly.

The Patterns of Breastfeeding

The majority of teenage mothers (81.25%) breastfed partially because the fear that breastmilk does not come out milk is not sufficient. Meanwhile, one teenage mother (6.25%) predominantly breastfed because the infants have been given pre-lacteal food such as Javanese sugar water by the labor force, which is then replicated by the parent (mother) of the teenage mother when the infant was already at home. The majority of teenage mothers (93.75%) are still living with parents. They are still dependent on their parents and less mature in deciding a problem, Thus become one impact of the early marriage.22 In fact, the results of this study indicate that in addition to supporting teenage mothers to breastfeed, parents (mother) also has to suggest the provision of pre-lacteal food, complementary food or breast-milk substitution too early.

A total of 2 other teenage mothers (12.5%) stopped breastfeeding. A teenage mother who stopped breastfeeding (6.25%) with the reason that breastmilk only came out 1 month due to the flat nipples, cognitively stated that breastfeeding is mandatory if the breastmilk comes out. Another, teenage mother who stopped breastfeeding (6.25%) due to the nipple interference (sore nipples, mbangkak'i or swollen breast, blood and pus burst out of the breast), cognitively also stated that breastfeeding is mandatory when there is no nipple interference. The sore nipple is caused by the fault of feeding techniques in which the baby has not been breastfed appropriately. If the baby is fed only on the nipple, the baby will get a little milk because the baby's gums do not press the lactiferous sinus area, while the mother will experience the sore on the nipples. The fault of the baby who is not breastfed appropriately is the result of the use of pacifier when the baby is still learning to suckle. The use of baby pacifiers can cause nipple confusion (nipple confuse) because the sucking mechanism is different between the nipple and pacifier.21

According to the WHO definition, breastfeeding patterns are categorized into three types, namely exclusive breastfeeding, predominant breastfeeding and partial breastfeeding. Exclusive breastfeeding means to not give the baby other food or drink, including water, other than breastfeeding (except medicines and vitamin or mineral drops, breastmilk is also allowed). Predominant breastfeeding is feeding the baby, but also providing a little water or water-based beverages, such as tea, as a pre-lacteal food before the breastmilk comes out. Partial breastfeeding is feeding the baby and given artificial food such as formula milk, porridge, or other foods before the baby was six months old. That food is both supplied continuously or given as a pre-lacteal food.23 Feeding too early can cause problems in the baby's stomach, resulting in the inhibition of the absorption of nutrients. Infants can experience the decrease of nutrition.24

The Infants Food Intake

The infants food intake can be seen from the following table 2.

Table 2. Infants Food Intake

|

Infant of Teenage Mother (ITM) |

Sufficient Level of Energy |

Sufficient Level of Protein |

Sufficient Level of Carbohydrate

|

Sufficient Level of Fat |

|

||||

|

% |

Category |

% |

Category |

% |

Category |

% |

Category |

|

|

|

ITM1 |

98,4 |

Moderate |

106,0 |

Adequate |

110,9 |

Adequate |

101,9 |

Adequate |

|

|

ITM2 |

87,8 |

Moderate |

86,7 |

Moderate |

105,6 |

Adequate |

75,9 |

Subordinate |

|

|

ITM3 |

101,9 |

Adequate |

103,9 |

Adequate |

103,1 |

Adequate |

102,4 |

Adequate |

|

|

ITM4 |

102,7 |

Adequate |

104,9 |

Adequate |

111,1 |

Adequate |

97,7 |

Moderate |

|

|

ITM5 |

108,3 |

Adequate |

117,6 |

Adequate |

111,1 |

Adequate |

105,7 |

Adequate |

|

|

ITM6 |

104,8 |

Adequate |

100,7 |

Adequate |

125,3 |

Adequate |

89,8 |

Moderate |

|

|

ITM7 |

100,9 |

Adequate |

103,6 |

Adequate |

102,8 |

Adequate |

100,3 |

Adequate |

|

|

ITM8 |

103,1 |

Adequate |

111,4 |

Adequate |

107,1 |

Adequate |

99,9 |

Moderate |

|

|

ITM9 |

103,2 |

Adequate |

101,8 |

Adequate |

116,3 |

Adequate |

93,9 |

Moderate |

|

|

ITM10 |

92,3 |

Moderate |

135,0 |

Adequate |

96,4 |

Moderate |

81,8 |

Moderate |

|

|

ITM11 |

109,4 |

Adequate |

111,4 |

Adequate |

110,6 |

Adequate |

109,9 |

Adequate |

|

|

ITM12 |

103,5 |

Adequate |

105,7 |

Adequate |

104,7 |

Adequate |

104,0 |

Adequate |

|

|

ITM13 |

103,2 |

Adequate |

118,9 |

Adequate |

107,2 |

Adequate |

97,9 |

Moderate |

|

|

ITM14 |

103,4 |

Adequate |

98,7 |

Moderate |

126,2 |

Adequate |

86,0 |

Moderate |

|

|

ITM15 |

79,3 |

Subordinate |

147,4 |

Adequate |

88,4 |

Moderate |

51,2 |

Deficit |

|

|

ITM16 |

104,7 |

Adequate |

156,9 |

Adequate |

105,9 |

Adequate |

105,2 |

Adequate |

|

Table 2 shows that the majority of energy intake infants (75%) categorized as the adequate level. The majority of protein intake infants (87.5%) were also adequate. No different, the majority of carbohydrate intake infants (87.5%) were in a adequate level. Based on their fat intake, as many as seven infants (43.75%) were on a adequate level, 7 infants (43.75%) were in the moderate category, and 2 infants (12.5%) experienced shortages of fat intake.

Based on the food intake, it is known that there was 1 infant (6.25%) who lacked the fat intake and 1 infant (6.25%) had a shortage of energy intake and fat. Both infants were not breastfed because her mother had stopped breastfeeding and replace it with the breastmilk substitution and complementary food. Both infants were deficient in nutritional intake due to the improper provision of complementary food and breastmilk substitution, which was too small in quantity and watery.

Breastmilk is the best food that meets the nutritional needs of infants for optimal growth and development. If the baby is getting enough breastmilk, the water and nutrients in breastmilk will be fulfilled.25 Carbohydrates in the breastmilk is lactose in which the fat contains a lot of polyunsaturated fatty acid, main protein is easily digested lactalbumin, the vitamin and mineral content is sufficient. Energy is supplied mainly by carbohydrates and fats. Lactose is a type of carbohydrate that is beneficial for the baby's digestive tract. Minimal fat should provide 30% of energy. Of breastfeeding, the baby absorbs about 85-90% of fats.26 Fat is needed in the absorption of vitamins A, D, E and K as well as the sources of essential fatty acids. Essential fatty acid deficiency can lead to developmental and growth delays.25

Infectious Diseases

The results showed that during the first months of the study, there was only 1 out of 16 infants (6.25%) who never got an infectious disease such as fever, cough, runny nose, or diarrhea. A total of 9 infants (56.25%) got a fever in which 4 of them got the fever after immunization. A total of 7 infants (43.75%) got cough and 10 infants (62.5%) got cold. There were 3 infants (18.75%) who got diarrhea in which 2 of them experienced it when their mother tried to give complementary food or early breastmilk substitution, and one other infant experienced it because of the replacement of the brand of complementary food.

Breastmilk protects the baby from the infectious disease.25 Breast-milk contains immunoglobulins that can provide protection against the disease.20 According to research results conducted by Rahmadhani, et al in Padang, exclusive breastfeeding is associated with an acute watery diarrhea.27 According to the research conducted by Widarini & Sumasari in 2009 in Bandung, exclusive breastfeeding is associated with the incidence of Upper Respiratory Tract Infection.28

The Nutritional Status of the Infants

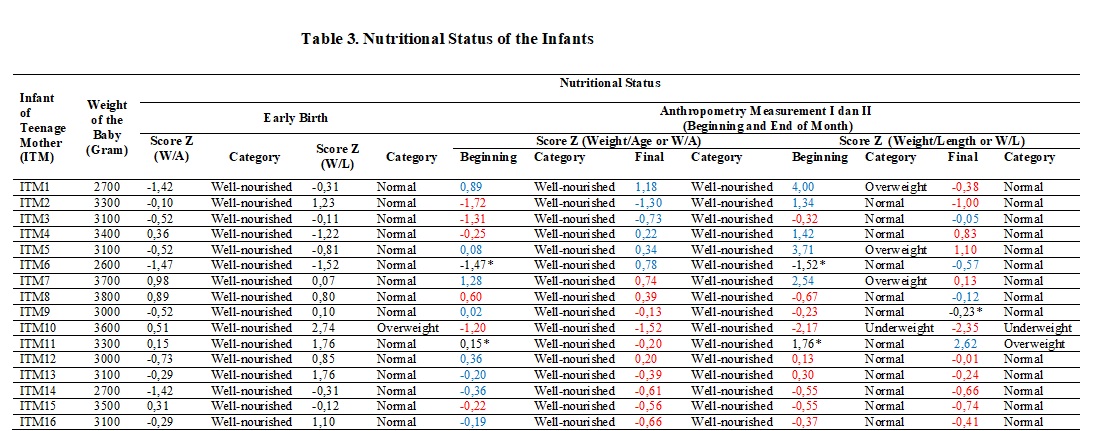

The data of the infants nutritional status can be seen in table 3.

Note :

Blue = Increasing

Red = Decreasing

* = Stable

Table 3 shows that none of the infants with deficit of birth weight. At the early birth, all infants (100%) were well-nourished (index W/A). Based on the index of Weight/Length (W/L), the majority of infants (9.75%) had normal nutritional status and 1 infant (6.25%) had overweight. According to the nutritional status of adolescent mothers breastfeeding, the majority of teenage mothers (81.25%) had normal nutritional status, 12.5% of teenage mothers had overweight, and another one (6.25%) experienced obesity. According to the research carried out by Karima & Achadi in 2012 in Jakarta, pre-pregnancy weight and maternal weight gain during pregnancy has a significant relationship with birth weight of the baby.29 Whereas, the nutritional status of the mother during breastfeeding is the effect on the nutritional status of the mother before and during the pregnancy.30

Based on the index of Weight/Age (W/A) from the early birth until the anthropometric measurements I and II, all infants (100%) stayed well nourished. Nevertheless, based on the score Z of W/A, there were 9 infants (56.25%) had the Z score decreased (6 infants got the Z score increased and subsequently decreased and 3 infants got the Z score decreased). Other, 2 infants (12.5%) got increased, 3 infants (18.75%) got the Z score decreased and then increased again. Otherwise, there were 2 infants (12.5%) who got the anthropometric measurement I result in the same as at the early birth (anthropometric measurements I was performed when those two infants were 0 day old). Among of them, there was 1 infant increased the Z score and the other got the Z score decreased on the anthropometric measures II.

Based on the index of Weight/Length (W/L) from the beginning of the birth until the anthropometric measurements I and II, the majority of infants (68.75%) remained as normal nutritional status, 3 infants (18.75%) got the nutritional status from normal to overweight to normal again, 1 infant (6.25%) got the nutritional status of overweight to underweight, and 1 infant (6.25%) got the nutritional status of a normal to overweight. Despite the fact that the majority of infants (68.75%) remained normal nutritional status, but based on the score Z of W/L, there were 11 infants (68.75%) got the Z score decreased (5 infants or 31.25% had the Z score increased then decreased and 6 infants or 37.5% had more the Z score decreased). Other, there were 2 infants (12.5%) got the Z score decreased, then increased again and 1 infant (6.25%) got the Z score decreased, then subsequently stable. On the other hand, there were 2 infants (12.5%) who got the anthropometric measurements I result in the same as in the early birth (anthropometric measurements I was carried out when the two infants were 0 day old). Both of these infants had the Z score increased on anthropometric measurements II.

The results of this study were in line with the results of research conducted by Ridzal, et al in Makassar in 2013 which showed that children exclusively breastfed and children not exclusively breastfed have the same chance to have a adequate nutritional status, subordinate nutrition, and even malnutrition.31 The causation of the nutritional problems is multi-factorial. Nutritional problems are mainly due to poverty, lack of availability of food, subordinate sanitation, lack of the knowledge about nutrition, balanced diets, and health.12 However, a number of sufficient breast-milk results in the proportional weight.21