Methods

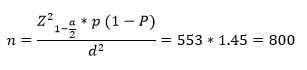

This is a cross-sectional study which is the analytical descriptive type conducted on the elderly of Sanandaj in 2018. Sanandaj is the capital of Kurdistan province in western Iran. According to the latest national census in 2016, the total population of the city is estimated at 865000 about 82000 of which are elderlies. We determined the sample size using the following formula and considering p = 50 (utilization of the health services), 5% accuracy and 95% significance level equal to 400 people, which was multiplied by 2 due to the use of stratified sampling. The final sample size was 800 people.

We selected the elderly via Stratified two-stage cluster sampling. First, we randomly selected 20 clusters (10 urban centers and 10 rural bases) from the comprehensive center of urban health and rural bases of Sanandaj, and from the population of the elderly covered by each center and base, 40 elderly people were randomly selected. We completed the questionnaire by making an appointment and visiting the household. We should note that written consent to participate in the study and having the appropriate mental strength of the elderly were the conditions for entering the study. We collected the required information through the Utilization Health Services questionnaire, which is a valid and reliable questionnaire designed by the National Institute of Health Research of Iran[12]. The questionnaire comprises three sections. The first section was demographic and contextual information, which included age, gender, occupation, education, employment status, basic insurance type, supplementary insurance status, and place of residence. The second part included the economic situation of the individual's family. The economic status of the individual's family was investigated through the home assets index (percent of the households that own house, computers, washing machines, dishwashers, vacuum cleaners, refrigerators, freezers, fridge freezers, car and internet access) and using the principal composition analysis method.

Based on Asset index, the study population was divided into 5 very poor, poor, moderate, rich and very rich quintiles (1 = poorest, 5 = richest). The third section was related to the questions of need, seeking and utilization of health services:

Have you felt the need for outpatient health care (over the past 30 days) and hospitalization (over the past 12 months)? Yes / No

Did you go to the health center to receive these services? Yes / No

Could you receive these services after referring to the health center? Yes / No

What were the reasons for not referring or not receiving services after referring to the health center?

Measurement of socioeconomic inequality in outpatient and inpatient services

The Wagstaff concentration index and concentration curve was used to measure the socioeconomic-related inequalities in outpatient and inpatient care[13]. In each of them, we examined the need, seeking and use of outpatient as well as the need, seeking and use of inpatient care. The Wagstaff concentration index takes value between − 1 and + 1; if its value is negative (positive), the outcome variable is more concentrated among the poor (rich). The concentration index plots the cumulative percentages of population ordered by socioeconomic status in x-axis against the cumulative percentage of outcome variable in y-axis. If the concentration curve lies under perfect equality line; the outcome variable is more prevalent among socioeconomically advantaged individuals and vice versa[14].

The Chi-Square Test and the Fisher's exact test were used to examine the relationship between independent variables including demographic variables and dependent variables, including the perceiving of the need and seeking the perceived needs of outpatient and inpatient services. Also, to determine the relationship between independent variables and the consequence variable (perceiving of the need, seeking inpatient and outpatient care) was calculated using multivariate logistic model regression, Adjusted Odds Ratio (OR) and confidence interval (CI). Statistical tests were performed using STATA software package