Results

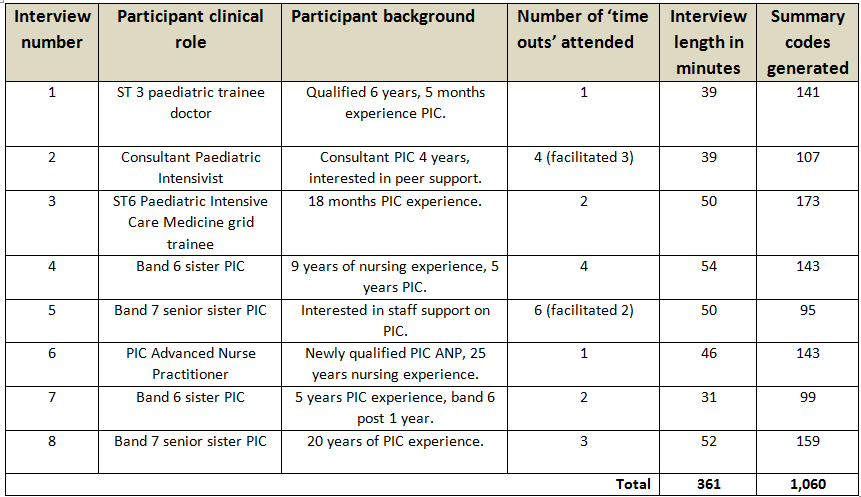

8 semi-structured interviews were carried out lasting between 30 and 60 minutes. This generated 361 minutes (6 hours) of transcribed material. Participants’ level of PIC experience ranged from 5 months to 25 years (table 1). 1,060 summary codes generated for thematic analysis developed into a thematic map (figure 2).

Table 1. Participant summary, interview length and summary codes generated

Key themes

- Context and culture in which traumatic incidents and time outs are embedded; hierarchy, local politics and triggers.

The impact of hierarchy and local politics upon the nature of incidents and the PIC response featured in every interview. One participant highlighted that “Most of the problems here come from… the perception that this… is not going anywhere…” showing how complex the PIC environment can be for staff looking after children whose chance of recovery is poor.

Another participant felt they experienced a “witch hunt” following the successful resuscitation of a child.

There were examples of hierarchy being protective, with the majority of ‘time out’ meetings instigated by consultants as “there was a felt need for a meeting”. Consultants can instigate formal peer support and seemed to be highly regarded for doing so. One junior participant describes the consultants in almost superhuman terms:

“I don’t know how people do this job all time, because it’s been .. it’s quite a hard job.. lots of children dying”.

Hierarchies were being broken down by ‘time out’ meetings. A participant discusses the benefit of everyone being invited to speak during the ‘time out’ meetings:

“ifeverybody is seen to make a contribution and everybody’s contribution is valued then hopefully it will become … easier”.

Another participant highlights how breaking down hierarchies helps peer support:

“it’s not just about being junior staff or senior staff, you know, everybody is vulnerable in a

certain way”

Triggers for needing a ‘time out’ were numerous. Common themes included complex congenital heart surgery, conflict with families, death of long-term PIC patients, airway emergencies and communication failure.

- Pragmatics of organising and evaluating ‘time outs’; facilitating, organising and meeting outcomes

Participants varied in their feelings towards being able to facilitate and lead a ‘time out’ meeting. A range of responses were captured; from “any idiot can run the ‘time out’ meeting…” through to “going into a room with stressed people they might feel .. what can of worms is this going to open?”

The act of going home was important for participants, as they physically distanced themselves from potential sources of trauma. However, on leaving PIC staff are left to deal with traumatic incidents alone. Staff dwell on stressful events and may leave work not fully understanding what has happened, leaving them open to misinterpretation and inappropriate self-blame. One participant observed:

“I think the debriefing process meant that rather than taking that home with him or feeling that he was to blame …. you can’t take that horrible experience on and panic every time …, you need to take it and know how to manage it next time”

Another participant describes the staff response following an intense incident towards the end of a night shift:

“we stayed an extra half hour after our shift ….I think we all needed to .. I don’t think anyone would have slept otherwise”

A recurring theme throughout the interviews was how clinical learning and emotional coping went hand in hand. The ‘time out’ meetings covers both elements, as described by one participant:

“People have a chance to say the reason we stopped was ... this… it was futile and not in the child’s best interests, people automatically go away with a better understanding and feeling better”

The challenge of running the ‘time out’ meetings on the same shift was discussed. A pragmatic approach has been to organise them days later, often when staff are not on shift. This was deemed sub-optimal, as staff would not be reimbursed for commuting time and some staff felt benefit from discussing the event before they went home. The impact on the individual should be considered:

“I think ideally people shouldn’t be coming in on their own time … I wonder whether that makes it bigger in your head”

Participants had mixed feelings on their ability to facilitate ‘time out’ meetings. A number of participants suggested more ‘training’ to be able to facilitate meetings. Supervised facilitating of ‘time out’ meetings would help build participants confidence to lead meetings independently. Facilitating was seen as a job for a confident, senior member of staff:

"I wouldn’t be comfortable at this moment in time to lead .. if I .. spent a day with X and she explained, … what I needed to do ...then I feel better at doing it”.

- Position of valued clinical psychologists, separate from the ‘time outs’

Participants held clinical psychologists in high regard, but with uncertainty around their role and how best they should support PIC staff “they’re the ones with the training in ... people dynamics ...I think they are probably a good addition to our unit …”

They provide one to one support on an ad hoc basis. Participants were uncertain regarding their input in group support sessions on PIC, such as ‘time out’ meetings with the concern that “If I felt I needed psychological support I wouldn’t want to access it in a room full of the people I work with….”

Some participants suggested they were a good resource for other people to use, but not themselves as they are “not usually one who stresses”. Participants appreciated that they were present on the unit to support staff if needed:

“you don’t always know that you need the support do you…., part of what they are doing is to help you develop coping strategies”.

The relationship between ‘time out’ meetings and clinical psychologists was developing as they were a recent addition to the department at the time of the research. Participants felt it unfair for clinical psychologists to lead ‘time out’ meetings, as they lack appropriate nuanced clinical knowledge:

“because if the person is saying ….I can’t deal with, this is the thing I can’t get over, and then this person has no idea what they are talking about… it’s a clinical dilemma….”

- Reflections on coping and resilience; fear and blame

A variety of powerful responses were seen in participants, notably blame, fear and concerns around litigation. Participants felt sharing thoughts and feelings on a stressful situation can help them cope, suggesting “ … you’ve got to share an experience… to move it on..”

One participant described her thoughts on working on PIC: “There are people that are given a rotation in PICU, that is their worst nightmare……it’s a very steep learning curve … you are kind of mentally prepared for the job before you start…”

Nursing participants discussed intense feelings of personal blame, more so than medical staff. A participant with both nursing and medical experience reflected that “the medical world is a lot more supportive”. One nurse reflected on a recent event:

“the worst thing that can happen to you is an accidental extubation, it’s horrendous, you feel so guilty”.

- Process of attending a time out and its impact – both positive (clinical knowledge and the ability to cope) and negative (damaging if inappropriately run); learning conversations, emotions and potential conflict

All participants valued the ‘time out’ meetings and felt the model worked for staff support locally. One participant described the meetings as a way of “nipping in the bud….” staff angst and stress after critical incidents. When run in the suggested format, ‘time out’ meetings had a positive impact on clinical knowledge and on the ability of staff to cope. A participant made the following observation:

“ when you see people that have been to ‘time out’ meetings .. their shoulders are a bit lower …… I’m not going to say they are smiling …. but some of the stress has gone…”

There were examples of clinical learning coming from ‘time out’ meetings, such as this PIC trainee’s reflection:

“we often ask for these things that other people do, and maybe… that it’s not always as simple ….”

When inappropriately run they have the potential to be damaging. One participant described “three fairly different experiences”. In one instance she felt a ‘time out’ meeting was organised to give negative feedback on a clinical situation:

“it was very much like you should have done it differently and it was a very horrible experience...”

Another meeting occurred “following the proper format” for a ‘time out’. A patient had deteriorated on the high dependency unit and an emergency call had not been put out. The discussion was different, in a more supportive manner:

“…. it was never like ‘oh you should have done that‘, it was like maybe… we should put them out cos maybe you can get more help quicker”.

Participant validation

5 out of 8 participants responded, who agreed that the thematic map was an accurate representation of what was discussed. One participant presumed that “themes around support and learning would have been more strongly represented”.