Tables

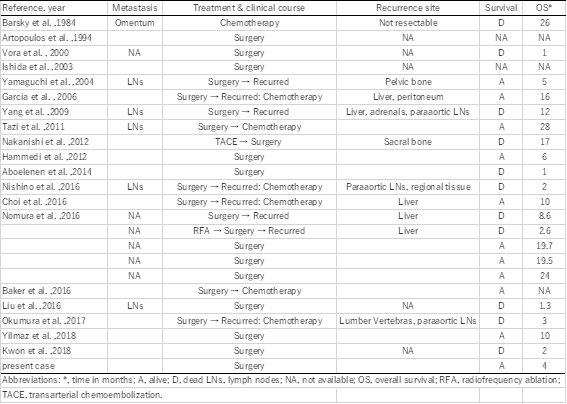

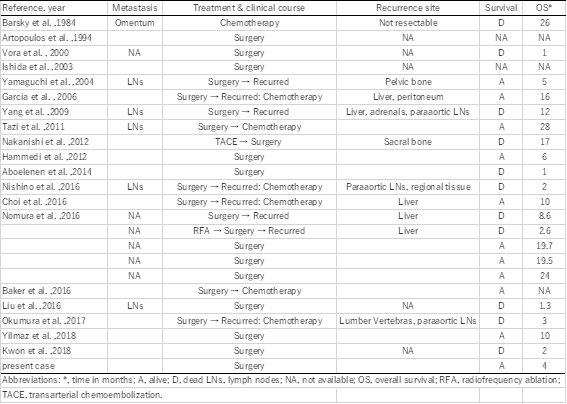

Table.1 Clinicopathological profiles of 25 reported patients with HCC–NEC.

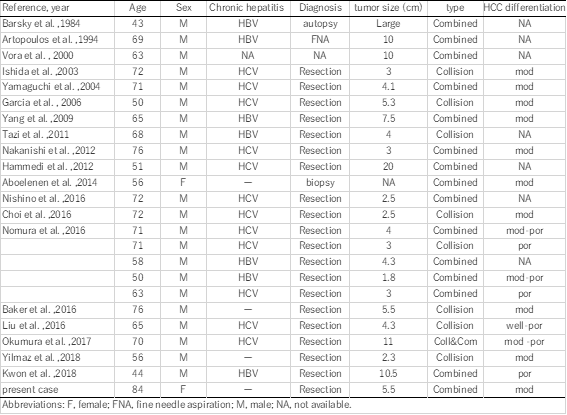

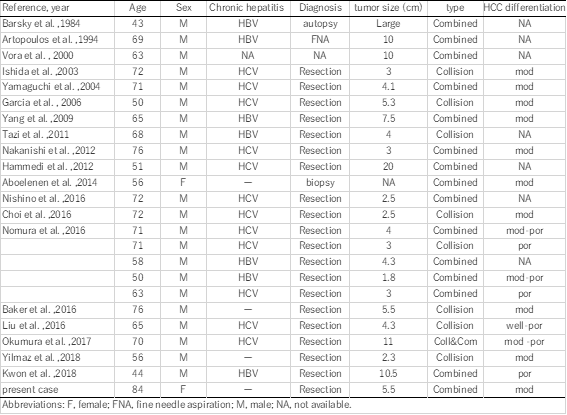

Table 2. Treatment and prognosis of 25 reported patients with HCC–NEC.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-96112/v1

Background: Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) can grow in a mosaic pattern, often combined with various non-hepatocellular cells. However, HCC combined with a neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) component is very rarely reported, and its clinical features, origin, diagnosis and behavior have not been established. In the literature, mixed HCC–NEC tumors are categorized as either collision type or combined type, depending on their microscopic features. Here we report a patient with a combined-type HCC–NEC tumor.

Case presentation: An asymptomatic 84-year-old woman was found to have a solid mass in the right lobe of her liver. Laboratory and radiologic examinations showed findings typical of HCC, including arterial-phase enhancement, and portal- and delay-phase washout. She was preoperatively diagnosed with HCC, and treated with partial laparoscopic hepatectomy of her S5 segment. The tumor was 5.0 × 6.0 cm in diameter, and was predominantly HCC, partly admixed with a NEC component. A transitional zone between the HCC and NEC tissues was also observed. The tumor was finally diagnosed as a combined-type primary mixed NEC–HCC tumor. After the diagnosis, the patient underwent somatostatin receptor scintigraphy to look for the primary NEC lesion, but no accumulations were found in any other part of her body. She has been free of recurrence for 6 months since the surgery.

Conclusion: Mixed HCC–NEC tumors are very rare. Correct diagnosis requires multidisciplinary collaboration. Accumulating cases is needed to help understand their exact pathology, diagnosis and treatment.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common liver malignancy,. It is composed of tumor cells with hepatocellular differentiation and cytological variants [1]. HCC often grows in a mosaic pattern, in which various cell types are arranged in different architectural patterns within a large tumor. HCC can occasionally combine with other non-hepatocellular cell types, of which the most common is HCC combined with hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma [2]. In contrast, neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) in the liver is rare, and usually arises as a metastasis from other organs [3]. As primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma (PHNEC) is particularly rare, combined primary HCC with PHNEC is even more rare. Combined PHNEC–HCC tumor histology is categorized into two types [4–6]: the collision-type tumor, in which two simultaneous but histologically distinct tumors are derived from the same organ with no histologic admixture; and the combined-type tumor, in which both components intermingle with each other, and cannot be clearly separated in the transitional area within a single tumor nodule. Here we present a patient with a combined PHNEC–HCC tumor with a favorable prognosis, and we provide a literature review of reported cases.

An 84-year-old Japanese woman with no history of hepatitis came to our institution because of a large solid mass in her right hepatic lobe that had been detected by computed tomography (CT) at another clinic. She had no specific symptoms, such as abdominal discomfort. Results of routine laboratory and liver function tests were within normal values. Her tests for serum hepatitis B surface antigen/antibody, hepatitis C antibody and hepatitis C virus-RNA were negative. Her serum alpha-fetoprotein level was high at 399 ng/mL, and protein induced by vitamin K antagonist-Ⅱ was 43 mAU/mL, i.e. a little elevated. Other tumor markers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen19-9 were within their normal ranges. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CE-CT) revealed a solid 48 × 43-mm mass at her hepatic segment 5. In the dynamic study, the lesion showed late arterial-phase contrast enhancement (Fig. 1A), venous-phase contrast washout, and peripheral enhancement (Fig. 1B). Her liver EOB-magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) dynamic study showed similar features. The chemical-shift MRI phase indicated that the tumor mostly consisted of fatty tissue (Fig. 1C). Diffusion-weighted imaging showed a high signal image at the ventral side (Fig. 1D). As these findings are typical of HCC, the patient was preoperatively diagnosed with HCC, and underwent a laparoscopic partial hepatectomy and cholecystectomy, without additional lymph node dissection.

Macroscopically, the tumor seemed solid, well-demarcated and encapsulated, and was whitish-yellow in color with hemorrhagic and necrotic changes inside. It measured 55 × 45 × 40 mm (Fig. 2A). Microscopically, the tumor showed both HCC and NEC components. The largest part of the tumor showed atypical cells with trabecularly-arranged eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 2B). Immunohistochemically, these atypical cells were diffusely positive for glypican-3 (Fig. 2C), but negative for chromogranin A and synaptophysin (Fig. 2D and 2E). The ki67 labeling index was approximately 10% (Fig. 2F). These histological and immunohistochemical features indicated moderately differentiated HCC. However, the grossly white-to-grey component was distributed from the center to the periphery of the tumor. This component was composed of a sheet-like arrangement of atypical cells with a high nucleus/cytoplasm ratio and many mitotic figures (Fig. 2B). The atypical cells in this area were immunohistochemically positive for synaptophysin and chromogranin A (Fig. 2D, E), but negative for glypican-3 (Fig. 2C). Their ki67 labeling index was approximately 80% (Fig. 2F). These histological and immunohistochemical features indicated NEC. The part of the tumor between the HCC and NEC components also showed atypical cells with enlarged nuclei and relatively broad cytoplasm (Fig. 3A), which were positive for both synaptophysin and glypiccan-3 (Fig. 3B, C), and seemed to be the transitional area between HCC and NEC. Based on these features, and the absence of a primary NEC lesion outside of the liver, we diagnosed it as a combined PHNEC–HCC tumor.

The patient had a good postoperative course. One month after her surgery, she underwent somatostatin receptor scintigraphy to look for the primary NEC lesion. The examination showed no somatostatin accumulation in any other part of the body, which indicated that the NEC component was not metastatic. The patient is still alive 6 months after the surgery, with no sign of recurrence or metastasis.

Primary hepatic NEC is a very rare tumor, even among gastro-enteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (GEP-NEN); its incidence is reportedly 0.3% among all NEN, and 0.46% among primary hepatic malignancies [7]. As the liver is the most frequent site of NEN metastases from other organs, a systemic search for the primary lesion is necessary when hepatic NEN was suspected, considering the rarity of PHNEC. In contrast, HCC, the most common liver malignancy, often coexists with other malignancies. The most common of these combinations, at 2.0–3.6% of all primary hepatic malignancies, is HCC with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma [8].

Although the exact origin of PHNEC is unclear, two hypotheses have been proposed [9, 10]: (a) neuroendocrine cells in the intrahepatic bile-duct epithelium undergo malignant conversion and become PHNEC; and (b) PHNEC originates from stem cells that dedifferentiated from other malignant hepatic cells and convert into neuroendocrine cells. The latter concept can explain the lesions with different carcinomas in one site, whereas the former can only explain the pathogenesis of single PHNEC tumors.

In the literature, these composite liver tumors are classified as either collision type or combined type. In collision-type tumors, the HCC and NEC grow as separable, microscopically distinctly compartments. In combined-type tumors, the HCC and NEC are closely intermingled, and a transition zone can be found. These tumors used to be categorized as “mixed adeno-neuroendocrine carcinoma (MANEC)” when at least 30% of either component is identified [10]. However, with the revision of the WHO Classification in 2019, “collision type” tumors, in which two components appear to be derived independently, simply adjoining with no observable mutual transition, were excluded from “mixed neuroendocrine neoplasm (MiNEN)” [11].

Concurrent occurrence of HCC and NEC is extremely rare. Including our patient, 21 published English-language reports of 25 patients with HCC with NEC components can be currently found. Clinicopathological profiles of these 25 patients are summarized in Table 1. These composite tumors were described as either collision type or combined type. In the present case, the two components were partly intermingled, and some portion of the HCC expressed neuroendocrine markers. Therefore, our case was classified as a combined-type MiNEN.

In the literature, combined type (n = 17) tumors were more common than collision type (n = 9; one patient had both collision- and combined-type tumors). Almost all the reported cases were preoperatively diagnosed as HCC, and re-diagnosed as combined or collision PHNEC–HCC tumors after resection, with only three cases diagnosed without surgery (by biopsy, fine needle aspiration, or autopsy); this shows the difficulty of correct preoperative diagnosis for these tumors.

In retrospective, preoperative images in the present case showed some conformity between images and pathology. In the preoperative MRI, the fatty tumor region, in which a low T1-weighted chemical shift in the dorsal tumor area is emphasized (which indicates fatty tissue and is thus highly suspicious of HCC), and the ventral area shows extremely high signal intensity in the diffusion-weighted image (typical for NEC expression) just coincide macroscopically with the distribution of HCC and NEC components in the tumor cut-surface, reflecting their mixture. Furthermore, distributions of these components show as if the HCC tumor had necrotic changes at its center, spreading to the tumor periphery. Previously, Yang et al reported a combined-type tumor in which poorly differentiated HCC focally expressed neuroendocrine marker [18], and resembled the present case. In our case, these findings seem to support the supposition that a moderate or poorly differentiated HCC transdifferentiates into a neuroendocrine phenotype, resulting in a combined HCC–NEC tumor.

The clinical significance of HCCs with NEC components is unclear. Several studies have shown that HCCs with NEC components are associated with aggressive behavior and dismal outcomes.

Mixed PHNEC and HCC lesions tend to have a poor prognosis. Of the 25 cases summarized, eight patients had recurrences, six patients died within a year after their surgeries, and only two patients were alive 2 years after surgery (Table 1). Although the number of reported cases is rather small, the 1-year cumulative survival rate of the patients was 53.0% in our literature review (prognosis not available for 3 patients). Among resected cases with recurrences or biopsy-confirmed metastasis, the NEC component was found in each case, which indicates that the NEC component behaves more aggressively than primary HCC, leading to a much worser prognosis. Therefore, identifying the neuroendocrine component, and assuring the patient receives proper treatment is important.

In conclusion, mixed PHNEC and HCC tumors are extremely rare. Further accumulation of case reports is required to clarify the features, diagnostic details and optimal therapy for combined PHNEC–HCC lesions.

CE-CT, contrast-enhanced computed tomography; EOB-MRI, ethoxybenzyl diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging; GEP-NEN, gastro-enteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma;; MiNEN, mixed neuroendocrine neoplasm; NEC, neuroendocrine carcinoma; PHNEC, primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma.

This study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for ethical approval was waived by the Tokai University Hospital Review Board.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

All data generated during this study are included in this published article.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Not applicable

All authors were involved in patient management and manuscript conception. AN and KH drafted the manuscript and revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

We thank Marla Brunker, from Edanz Group (https://en-author-services.edanzgroup.com/ac), for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Table.1 Clinicopathological profiles of 25 reported patients with HCC–NEC.

Table 2. Treatment and prognosis of 25 reported patients with HCC–NEC.